Music Notation History

This introduces you some basics about reading standard music notation. It is the only music notation for all instruments used internationally today. Horizontal lines to indicate the relative pitches of notes first appeared in the 11th century. This system has developed and evolved over time and has outlived all other forms of music notation invented in the last 3,000 years. As you learn how to read music notation, you are building on what generations of musicians have built to communicate their musical ideas across the centuries.

Musical Clefs

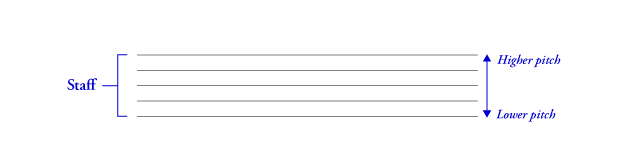

Standard music notation uses clefs placed on five horizontal lines (called the staff) to identify the pitch. Clefs include:

- The G or treble clef (for high-sounding instruments, and used for guitar transcriptions)

- The F or bass clef (for low-sounding instruments)

- The movable C clef (which can be placed anywhere on the staff to indicate the position of the middle C).

Here are the way the different clefs look in music notation:

Staff

All guitar music is written in a range identified by the treble or G clef. The treble clef appears at the beginning of each staff line. The notes are written on the lines and in the four spaces between the lines.

Notes and Pitch

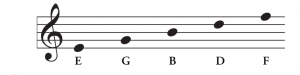

Notes appear on the staff to indicate pitch. Each line and space has a name, and a note appearing on a line or space takes that name. The notes on the lines are named E, G, B, D and F. (Remember this by saying “Every Good Baby Does Fine.”)

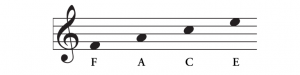

The notes in the spaces are F, A, C and E. (Remember this because it spells “FACE.”)

The musical alphabet uses the first seven letters of our alphabet: A B C D E F G. After this, the notes repeat: A B C D E F G. This second set sounds an octave higher. In other words, the distance from the A note up through the following seven notes is called an octave.

When played on a guitar, notes in standard music notation sound one octave lower than they would if played on a piano.

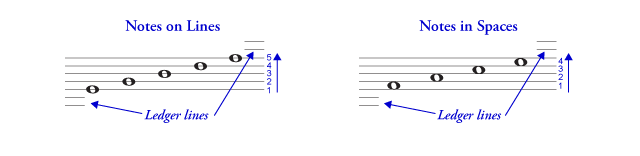

If a note is needed above or below the staff, ledger lines are added.

Rhythmic Values

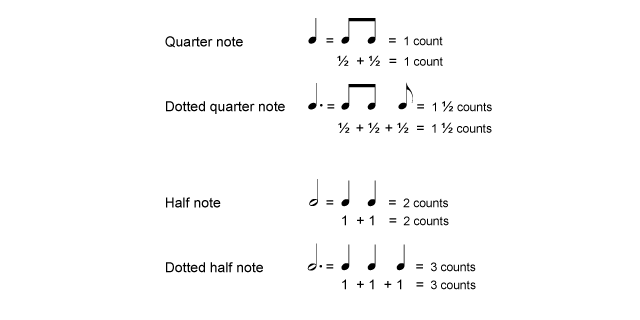

Notes that look different are held for different amounts of time and are counted as divisions against the time signature. For example, in 4/4 time there would be 4 quarter notes in one measure and each quarter note would be played for 1 beat.

A whole note equals four quarter notes. So, it would be held for a whole measure (four counts/beats) in 4/4 time.

A whole note equals four quarter notes. So, it would be held for a whole measure (four counts/beats) in 4/4 time.

A half note equals two quarter notes and is held for two counts.

A half note equals two quarter notes and is held for two counts.

A quarter note usually gets one beat/count (see Time Signatures).

A quarter note usually gets one beat/count (see Time Signatures).

An eighth note equals half of a quarter note,and gets 1/2 a beat.

An eighth note equals half of a quarter note,and gets 1/2 a beat.

Consecutive eighth notes are usually connected by a line.

Consecutive eighth notes are usually connected by a line.

In this example, you would play one note on the downbeat and the next note on the upbeat.

A sixteenth note equals half of an eighth note.

Consecutive sixteenth notes are usually connected by two lines.

Consecutive sixteenth notes are usually connected by two lines.

A dot added to any note increases its rhythmic value by one-half the original.

Thus, if a quarter note gets one beat, then a dotted half note gets three beats, a dotted quarter note gets 1 1/2 beats and a dotted eighth note gets three-quarters of a beat. The graphic below illustrates this.

Rests

Rests are periods of silence in music. Just as there is a variety of notes to indicate different lengths of sound, there are matching rests to indicate different lengths of silence.

A whole rest is a measured silence equal to a whole note in duration. This also indicates a full measure of rest in any time signature.

A whole rest is a measured silence equal to a whole note in duration. This also indicates a full measure of rest in any time signature.

A half rest is equal to a half note in duration.

A quarter rest is equal to a quarter note in duration.

An eighth rest is equal to an eighth note in duration.

A sixteenth rest is equal to a sixteenth note in duration.

A sixteenth rest is equal to a sixteenth note in duration.

How to Read Music “Sentences” – How Measures and Markings Help Organize Notes

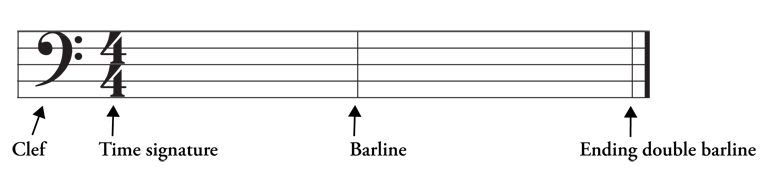

For written music, very small sections of music are organized into easily recognizable groups of beats or pulses. These small sections are called bars or measures and are indicated by a line across the staff. Time signatures indicate how many beats are grouped in each measure.

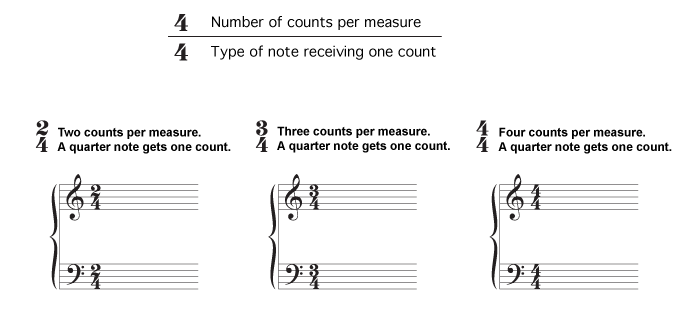

The time signature is found at the beginning of a piece of music and is given as two numbers, one on top of the other. The top number tells you how many beats per measure and the bottom number tells you the time value of each beat.

The end of a piece is indicated by two lines. Barline Ending double barline

Time Signatures

At the beginning of most songs is a time signature. Time signatures are divided into two basic types: simple and compound. Simple time signatures include 2/4, 3/4 and 4/4.

The top number of the time signature indicates how many counts per measure. The bottom number indicates what note receives one count (i.e. 4 means the quarter note gets one count and 8 would mean the eighth note gets one count). For example, the signature 2/4 tells you that there are two beats per measure and each quarter note gets one beat.

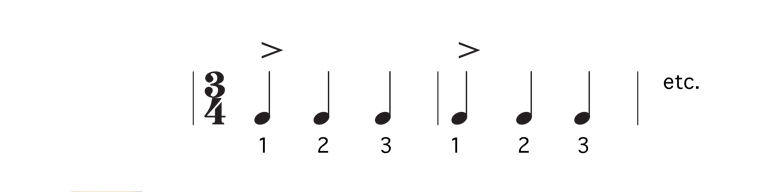

In 4/4, there are four counts to a measure and the quarter note receives one count. In 3/4, three counts are to a measure and the quarter note receives one count.

Notice on the next screen that the first beat of each measure is marked with an accent, since the strong or accented pulse is at the beginning of each bar.

Simple Time Signatures

The time signature 4/4 is often called common time and is often abbreviated with a “C” in place of 4/4.

4/4 time is considered a Simple Quadruple time signature.

3/4 Time is a Simple Triple time signature.

Compound Time Signatures

In the previous lesson, we learned that all simple time signatures are grouped with one strong beat per measure. Compound time signatures include those that have more than one strong pulse per measure and are divisible by three. Compound time signatures include 6/8, 9/8, 12/8 and 6/4. The time signature 6/8, for example, tells you that there are six beats per measure with each eighth note getting one beat. Additionally, 6/8 usually implies accented pulses on beats one and four. Thus, the time signature will feel like two groups of three beats with an accented beat beginning each group of three. Other compound signatures are given on the next screen. Notice there is more than one strong pulse per measure for each of these time signatures.

Asymmetrical Time Signatures

Asymmetrical signatures are rare in most popular music, but they can be found in some non-Western folk music and in jazz and classical music. Asymmetrical time signatures include those such as 5/4, 7/8 and 11/8, all of which possess unequal division of accented pulses. The signature 5/4, for example, is not divisible into even, symmetrical groups, but will be divided into asymmetrical patterns of either 3 + 2 or 2 + 3.

Tempo Marking

Here are the three most basic tempo markings:

- Adagio, which means “Slow, (or leisurely)”

- Andante, or “Walking pace”

- Allegro which is “Fast (or brisk)”

You will also find tempo markings which are used for changes of speeds:

- rit. or ritard. (ritardando) means that you should gradually play slower and slower.

- acc. or accel. (accelerando) implies that you should start playing faster and faster.

Dynamic Markings

Dynamic signs tell you the volume level at which the music should be played: loudly, softly, or in between. Dynamics create expression in music. Dynamic signs can be found throughout a musical composition. On the piano you usually see these in the space between the two staffs or underneath. A dynamic sign is in effect until the next dynamic sign appears.

Thank you for giving the info. It’ll help me bunch.

Your place is valueble for me. Thanks!